- Japanese Culture

What Is Rakugo? History, Appeal, and Three Beginner-Friendly Stories

2025.09.29

Many people know that rakugo is a storytelling art performed while seated, but aren’t sure about the details.

In recent years, thanks to popular manga like Shōwa Genroku Rakugo Shinju and Akane-banashi, as well as the rise of non-Japanese rakugo performers, rakugo has been attracting attention worldwide—and more people want to learn about it.

In this article, we’ll introduce what rakugo is, its history, and its unique appeal.

We’ll also explain the types and structure of rakugo, and highlight three beginner-friendly stories you can enjoy!

What Is Rakugo?

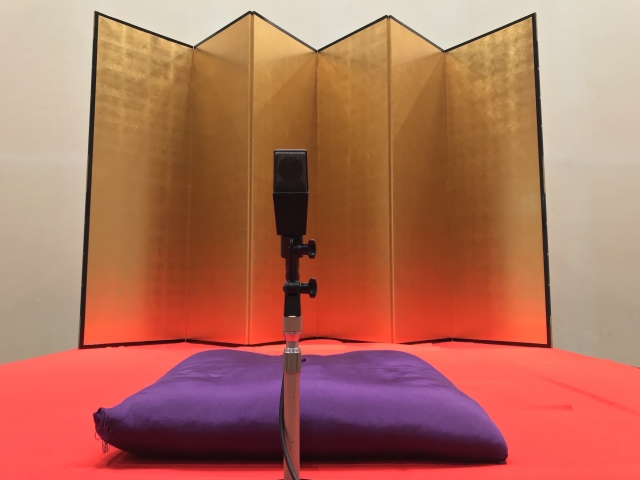

Rakugo is a traditional Japanese seated storytelling art in which a performer, called a hanashika, entertains the audience with humorous tales while sitting on a cushion.

Using just a fan (sensu) and a hand towel (tenugui), the storyteller switches skillfully between multiple characters through voice, timing, and gesture to unfold the narrative.

Because rakugo relies not on costumes or sets but on language and mime to spark the audience’s imagination, it is known as a traditional performing art that demands high-level verbal and performance skills.

The History of Rakugo

Rakugo is said to have originated in the late 16th century Azuchi–Momoyama period (安土桃山時代, あづち ももやま じだい / Azuchi–Momoyama jidai), when otogishū (御伽衆, おとぎしゅう / otogishū)—advisors on political and military matters—told humorous tales to soldiers.

To keep troops alert against night attacks, these advisors mixed comic elements into heroic war stories, helping stave off drowsiness.

From 1688 to 1704, performers such as Tsuyu no Gorōbee (露の五郎兵衛, つゆの ごろべえ / Tsuyu no Gorōbee) in Kyoto, Yonezawa Hikohachi (米沢彦八, よねざわ ひこはち / Yonezawa Hikohachi) in Osaka, and Shikano Buzaemon (鹿野武左衛門, しかの ぶざえもん / Shikano Buzaemon) earned money by telling amusing stories in public spaces, a style known as tsujibanashi (辻噺, つじばなし / tsujibanashi). They are regarded as the founders of rakugo.

By 1790, dedicated variety theaters called yose (寄席, よせ / yose)—traditional venues for variety arts such as rakugo (落語, らくご / rakugo), manzai (漫才, まんざい / manzai), and kōdan (講談, こうだん / kōdan)—emerged, bringing rakugo to a wide public and greatly boosting its popularity.

Types of Rakugo

Rakugo is broadly divided into two categories:

|

Koten Rakugo (Classical Rakugo) |

Comedic or sentimental stories passed down from earlier times, mainly created during the Edo to Meiji periods. |

|

Shinsaku Rakugo (New Rakugo) |

Works created from the Taishō period onward by performers and writers—stories that feel accessible to modern audiences. |

As popular entertainment, rakugo has evolved with the times.

Classical rakugo has a refined charm, polished over many years by generations of storytellers, while new rakugo often incorporates topical themes, making it easy and fun to enjoy.

★Also try reading:

What Is Kabuki, Japan’s Traditional Performing Art? | History, Appeal, and Where to Experience It

Structure of Rakugo

Rakugo is built around the following three elements:

|

Makura (Opening Banter) |

For about the first five minutes, the storyteller chats about everyday topics related to the main story to draw the audience into the rakugo world. |

|

Hondai (Main Story) |

The main story can be a comic tale (kokkei-banashi), a human drama (ninjō-banashi), or a ghost/monster story (kaidan-banashi). Traditionally, the main story begins when the performer removes their haori (kimono jacket). |

|

Ochi (Sage / Punchline) |

A clever twist or witty line that surprises the audience and ties the story together at the end. |

Each part has a purpose: the makura relaxes the audience, the main story immerses them in the narrative, and the ochi provides a satisfying finish.

The makura may also be used to choose a piece that suits that day’s crowd, or to teach key vocabulary needed to enjoy the main story.

Four Appeals of Rakugo

The appeals of rakugo can be summarized in the following four points:

- Savor Japan’s traditional atmosphere

- Enjoy Japan’s unique culture of humor

- Immerse yourself in staging that draws you into the story

- Appreciate the depth of the narratives

Below, we explain each point.

Savor Japan’s Traditional Atmosphere

Some yose theaters have been operating for over 150 years or retain classic wooden architecture, letting audiences feel Japan’s history as they watch.

You can also hear traditional drum cues: ichiban-daiko (played when doors open), niban-daiko (before the program begins), and hane-daiko (as people head home)—another hallmark of rakugo.

Enjoy Japan’s Unique Culture of Humor

Japanese humor often conveys wit indirectly through word choice, rather than through overt gags.

Rakugo embodies this cultural flavor—its distinctive rhythm and expressive language invite laughter, letting audiences experience a style of storytelling unlike that of other countries.

Immerse Yourself in Staging That Draws You Into the Story

Rakugo features staging that pulls listeners into the narrative world.

Through voice quality, intonation, facial expressions, gestures, and the expressive use of a fan and hand towel, the performer leads the audience to visualize each scene. Even the same piece can feel quite different depending on the performer’s approach.

Appreciate the Depth of the Narratives

Because many rakugo pieces have been handed down for generations, they offer notable depth.

As masters teach disciples, the stories are refined—from characters’ speech to the punchline (ochi)—creating a rich taste to savor. Some tales may seem merely humorous at first, yet depict complex emotions such as the joys and hardships of life, rewarding repeated listening.

【Beginner-Friendly】Three Rakugo Stories

Three rakugo pieces that are easy for beginners to enjoy are:

- Jugemu (寿限無)

- Manjū Kowai (まんじゅうこわい)

- Hatsu Tenjin (初天神)

Below are brief introductions to each.

Jugemu (寿限無)

The story begins with a man asking a temple priest for auspicious name ideas for his newborn son.

Unable to choose just one, he stuffs all of the priest’s lucky phrases into a single, comically long name.

Later, the boy—now a mischievous child—hits a friend on the head, leaving a bump. The friend runs to tell his mother, but by the time he finishes reciting the boy’s ridiculously long name and explaining what happened, the bump has already gone down. That’s the punchline (ochi).

Manjū Kowai (まんじゅうこわい)

A group of young men are chatting about what they fear: “Spiders,” “Snakes,” and so on. One fellow declares, “I’m terrified of manjū (sweet buns).”

Everyone laughs and decides to play a prank by piling up manjū to scare him.

But the man isn’t afraid at all—he happily eats them all. When asked, “So what are you really afraid of, then?” he replies, “Right now, a good strong cup of tea is the scariest thing of all.” That’s the ochi.

Hatsu Tenjin (初天神)

A father plans to visit a shrine and reluctantly brings along his son, who is notorious for begging. The father makes him promise not to ask for anything.

As expected, the boy starts pestering anyway, and the father finally buys him a big kite. When they go to fly it, the father becomes more absorbed than the son. The exasperated boy says, “If I’d known it would turn out like this, I never would’ve brought my old man!”—the story’s ochi.

How to Enjoy Rakugo

There are many ways to enjoy rakugo. If you’d like to enjoy it easily at home, watching DVDs is a great option. If you want the live atmosphere of a yose (寄席, よせ / yose) theater, we highly recommend visiting Japan to experience rakugo in person—at a yose, you can feel the performer’s very breath and presence, which pulls you even more deeply into the world of the story. If you’d like to hear rakugo in English, consider attending an English-language rakugo performance.

Recommended places to find rakugo on DVD

- YesAsia (North America site) – Ships Japanese media to U.S. customers from their NA storefront; their Global site explicitly redirects U.S. buyers to NA.

- Amazon.co.jp – Broad selection (many ship internationally). Example: NHK’s Tatekawa Danshi DVD+BOOK anthology.

Where to catch rakugo in English (Japan & beyond)

- Katsura Sunshine (勝⽥家サンシャイン) – Official schedule: Frequent English-language rakugo runs in Tokyo (Asakusa Mokubatei) and international tours; check dates and tickets here.

- English Rakugo Association (英語落語協会): Regular English and bilingual shows in Asakusa (often at the Asakusa Culture Tourist Information Center) with event listings and ticket links.

★Also try reading:

Deepen Your Understanding of Japanese Culture and Traditions! A Detailed Guide to 12 Iconic Traditions

Conclusion: What Is Rakugo?

Rakugo is a traditional Japanese storytelling art in which a seated performer (hanashika) plays multiple roles using only voice, gesture, a fan, and a hand towel to bring the narrative to life.

If learning about rakugo has sparked your interest in Japanese language and culture, why not try online lessons with Oku Sensei’s Japanese?

At Oku Sensei’s Japanese, experienced teachers provide personalized support, helping even beginners aim for practical, real-world Japanese.

Right now, we’re also offering a free 30-minute consultation—be sure to check it out!